Breaking the Mold: The Mix-and-Match Revolution of Franciscan Fine China

How a Bold Design Philosophy Transformed Tableware from Being Mundane to a Curated Masterpiece

How a Bold Design Philosophy Transformed Tableware from Being Mundane to a Curated Masterpiece

History has a curious way of turning necessity into art. In August 1939, when Gladding, McBean partnered with Max Schonfeld of the Max Schonfeld Co., they embarked on a journey that would forever change how we view and use tableware. Working in a modest laboratory setting, artisans experimented with a Belleek-inspired china casting body and an innovative glaze, resulting in an entirely new type of fine china. The production of a few initial pieces not only recouped development costs but also set the stage for a revolution in tableware design.

By 1941, Gladding, McBean had begun to establish its own identity—a distinct line of Franciscan Fine China shapes and patterns was emerging. Officially introduced in 1942, the collection was temporarily pared down during World War II, with production limited to pre-war designs. When the conflict ended in 1945, creativity reemerged, marked by the release of a solitary yet striking pattern—the Rossmore on the Merced shape.

The turning point arrived in 1946. Mary K. Grant, whose early visionary ideas had already influenced the line, was elevated from Lead Stylist to Chief Stylist and Designer. Alongside her, C.O. (Carl Odin) Moūness joined the design team and infused fresh inspiration into the process. That same year, the fine china Del Rey shape made its debut—the first entirely new shape since the war. By 1948, a burst of creativity had given rise to multiple patterns and the introduction of the Encanto shape, marking an era of design reawakening.

Embracing the Mix-and-Match Revolution

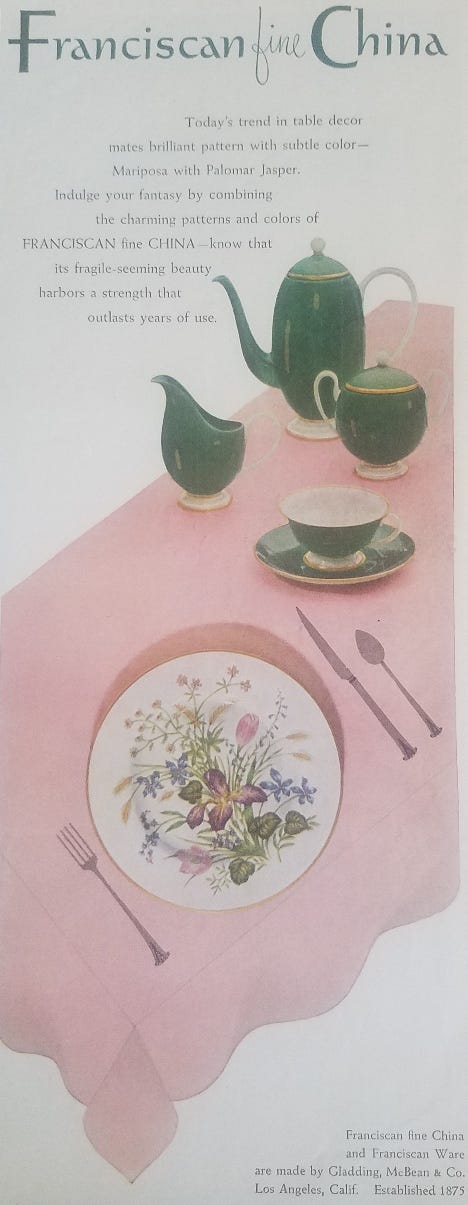

Amid this surge of innovation, Mary K. Grant began questioning the long-held notion that tableware needed to be sold strictly as matching sets. Enter Helen Sprackling—a consultant hired not only to craft compelling marketing materials but also to challenge and refine the very philosophy behind Franciscan Fine China. Sprackling’s expertise was well established, particularly through her book, Setting Your Table: Its Art, Etiquette, and Service, which provided readers with a comprehensive guide to table settings, entertaining, and the finer points of hospitality. Her deep understanding of the role of fine china in both formal and casual settings made her the perfect voice to champion Franciscan China.

Working closely with Grant, Sprackling championed the idea that each piece could stand on its own while seamlessly coordinating with others. The result was revolutionary: customers were invited to create personalized dining sets that broke free from tradition's rigidity. With a single guideline—to avoid mixing salt and pepper sets or cream and sugar bowls—homeowners were empowered to design table settings that truly reflected their individual style.

A Cultural Shift Rooted in History

Tableware has long been synonymous with uniformity and formality. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century homes, matching sets were the hallmark of sophistication. Yet even in those eras, practical necessities sometimes required families to replace broken pieces with mismatched items. These early adaptations laid the groundwork for a more deliberate mix-and-match approach that would eventually redefine fine china.

Early Individual Piece Sales

During the early-to-mid 20th century, most dinnerware was sold as unified sets, meaning every piece was identical. However, as consumer tastes began shifting toward more personalized styles, some manufacturers started offering dinnerware in individual pieces. Buyers could purchase items separately and arrange them to match their own aesthetic. Designers like Russell Wright, whose American Modern dinnerware debuted in 1939, played a pivotal role in this evolution. His designs—celebrated for their distinctive colors and individual appeal—helped launch a personality-driven, mix-and-match approach to tableware.

Experimentation Among Regional Manufacturers

In California during the early 1930s, experimental efforts in dinnerware production also hinted at a move toward individuality. Companies such as J.A. Bauer Pottery, Pacific Clay Products Co., and the Catalina Clay Products Division of Santa Catalina Island Co. began producing solid-colored dinnerware that naturally lent itself to a mix-and-match strategy rather than enforcing a strictly coordinated set. Although these innovations were initially driven by regional production experiments and market preferences, they laid the groundwork for the later, deliberate embrace of mix-and-match designs.

These early experiments with both uniform sets and individual pieces set the stage for the more refined and intentional approach that would blossom after World War II.

Transatlantic Tastes: Divergent Cultural Approaches

A closer examination of tableware aesthetics reveals a striking contrast between American and European traditions. In the United States, the post–World War II era saw a spirited rebellion against rigid formality. American consumers began to value individuality and practicality in their dining habits, which allowed designers like Mary K. Grant to challenge the long-held notion that fine china must always be sold as matching sets. A more relaxed, eclectic mix-and-match approach emerged as a means of self-expression—mirroring broader cultural shifts toward casual dining and creative lifestyles.

Across the Atlantic, European traditions held fast to formality for much longer. For centuries, matching dinnerware sets were synonymous with order, luxury, and social status standard epitomized by fine porcelain houses such as Meissen, Wedgwood, and Royal Doulton. While there were instances of individual pieces in utilitarian dinnerware, the realm of fine porcelain remained firmly anchored in coordinated design until modern influences gradually opened the door to mix-and-match concepts.

Design Pioneers: American and European Influences

Innovators on both sides of the Atlantic played key roles in redefining tableware aesthetics. In America, pioneers such as Mary K. Grant at Gladding, McBean and Russell Wright—with his trailblazing American Modern dinnerware—reimagined table settings by challenging strict uniform conventions. Their work celebrated individuality, practicality, and artistic flair. In Europe, despite a long tradition of formal dining, manufacturers gradually began integrating mix-and-match elements into their products. Accent details—like colored rims, delicate banding, and subtle overlays—provided a refined departure from absolute uniformity without compromising elegance. Designers such as Philippe Starck and Orla Kiely later injected modern playfulness into these traditions, underscoring a cultural evolution where the personal and eclectic converged with timeless craftsmanship.

Black Knight: An Early Pioneer in Mix-and-Match Fine China

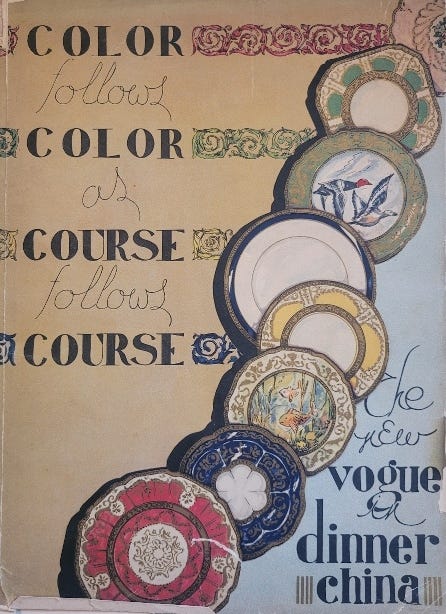

Though not part of the Franciscan lineage, Black Knight china represents one of the earliest deliberate forays into a non-uniform approach to fine china. Produced by Hutschenreuther China in Germany from 1925 to 1941, Black Knight china featured a trademark of a knight on horseback—a design intended to appeal to the American market in the wake of lingering anti-German sentiment after World War I. Within the Grant Family Collection at the Franciscan Ceramics Archives lies a fascinating artifact: the book Color Follows Color As Course Follows Course, The New Vogue in Dinnerware China by Helen Ufford and William F. Bruning (copyright 1930). Once owned by Mary K. Grant, this publication may have significantly influenced the emerging philosophy behind mixing and matching china patterns. In its reflective introduction, the authors write:

“During the all-too-brief period while the radiant symbol of festivities lies at each plate, the formal atmosphere is eloquently dispirited—an anti-climax comprising a monotonous procession of china in a 'matched' pattern, unvarying in color, unchanging in design.”

They advocate for using different patterns for serving various courses and suggest that for more informal occasions, brightly colored, contrasting patterns could enliven the dining experience. In this subtle yet influential way, Black Knight china hinted at the possibility of mixing and matching fine china long before it became a mainstream design philosophy.

Coordinated Collections: Precision in Pattern Pairing

As the mix-and-match philosophy took hold, it found clear expression in the specialized design lines of Franciscan Fine China. Even before later innovations, the Gold Band pattern was introduced in 1942, a gold-lined design that quickly became a coordination standard. Its timeless accents were crafted to complement any decorative pattern with similar gold detailing, ensuring a harmonious table setting.

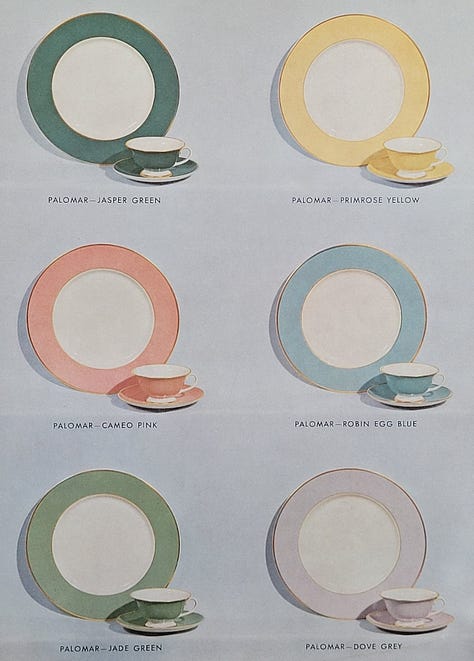

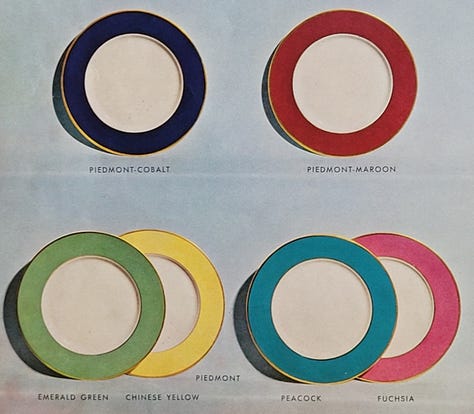

In 1946, the Piedmont line on the Del Rey shape made its debut. This collection featured colored rims accented by refined gold lining—a design element that coordinated perfectly with earlier decorative details. Then, by 1948, the innovative Palomar line on the Merced shape showcased an array of colored rims, integrating seamlessly with established decorative patterns. That same year, the pinnacle of coordinated design emerged with the coupe-shaped Encanto line. Offered in several solid colors and available with either gold or platinum banding over solid ivory, the Encanto line was meticulously crafted to pair effortlessly with all decorative patterns of its kind. Together, these coordinated collections embody the thoughtful interplay of color and design, ensuring that every element contributes to a cohesive and elegant narrative.

A Changing Tide: The Decline of the Mix-and-Match Philosophy

Despite the innovative surge fostered under Mary K. Grant's creative supervision, the mix-and-match approach began to wane after her departure from Gladding, McBean in November 1952. Her exit marked a significant shift in direction, and soon many of the pioneering fine china patterns were discontinued—among them, the brightly popular Piedmont line. By 1961, the Palomar pattern had been completely phased out.

The watershed moment came in 1962 when Gladding, McBean merged to form Interpace. Under the new management, the philosophy behind Franciscan Fine China shifted once again, reverting to designs and marketing strategies that favored stand-alone patterns over the creative interplay of mix-and-match configurations. This return to conventional aesthetics aligned with evolving market demands, and despite its pioneering legacy, the Franciscan Fine China line was eventually discontinued in 1977.

Resurgence: The Evolution of Mix-and-Match in the Late 20th Century

Although the innovation of designing fine china to mix and match was, in many ways, ahead of its time and somewhat short-lived, later decades witnessed a profound cultural shift. By the latter half of the twentieth century, the strict norm of purchasing matching sets of dinnerware, glassware, and flatware began to dissolve. As societal tastes evolved, formal dining—with its carefully curated, uniform table settings—gave way to more informal, expressive arrangements. Homes no longer featured separate, formal dining rooms isolated from the kitchen; instead, open and shared spaces became the norm.

In this new era, even households that maintained a dedicated dining room embraced eclectic table settings by combining pieces from different makers and collections. What was once a hallmark of formality slowly transformed into an opportunity for personalization. Whether for everyday meals or special occasions, mixing and matching tableware allowed homeowners to craft environments reflective of both individual style and broader cultural trends—melding tradition with modern creativity.

Legacy and Personal Expression

Today, the mix-and-match aesthetic of Franciscan Fine China is cherished by collectors, interior designers, and home enthusiasts alike. Each piece tells its own story, a nod to bygone eras, personal memories, and an evolving artistic vision. What began as a series of practical decisions has matured into an art form that beautifully balances tradition with modern creativity. The story of Franciscan Fine China invites you to embrace the beauty of curated imperfection—a journey where every dish on your table becomes a part of your personal narrative.

Enjoying My Free Substack Posts? Please consider Becoming a Paid Subscriber!

If you’ve been enjoying my free Substack articles, I invite you to support my work by becoming a paid subscriber. My latest paid subscriber post, Helen Sprackling, and the Rise of Franciscan Fine China: How One Consultant Shaped the Marketing of America’s Most Elegant Fine China, takes an in-depth look at Sprackling’s pivotal contributions to Gladding, McBean’s Franciscan pottery division.

Paid subscribers not only make my Substack possible, but they also support the Franciscan Ceramics Archive website, ensuring it remains free for everyone to explore. Your support helps preserve and share the rich history of Franciscan ceramics.

Thank you for being part of this journey!

Copyright Notice

© 2025 by James F. Elliot-Bishop. All Rights Reserved.

This article, Breaking the Mold: The Mix-and-Match Revolution of Franciscan Fine China, is the sole property of James. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the author.