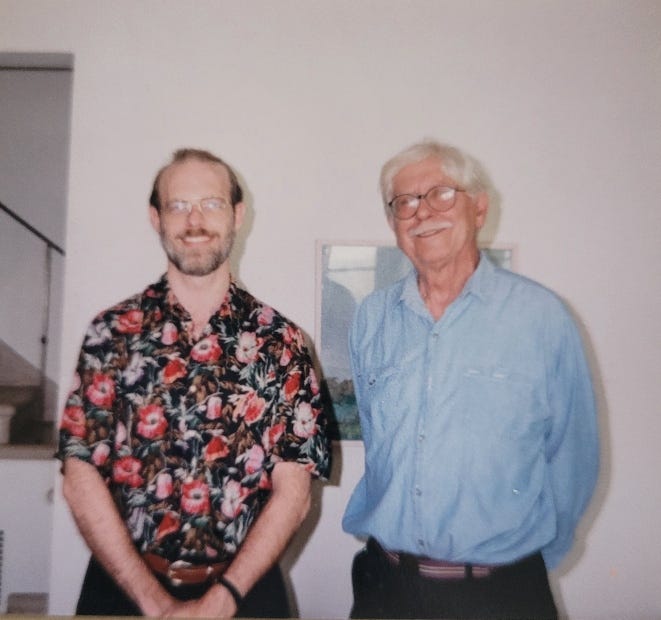

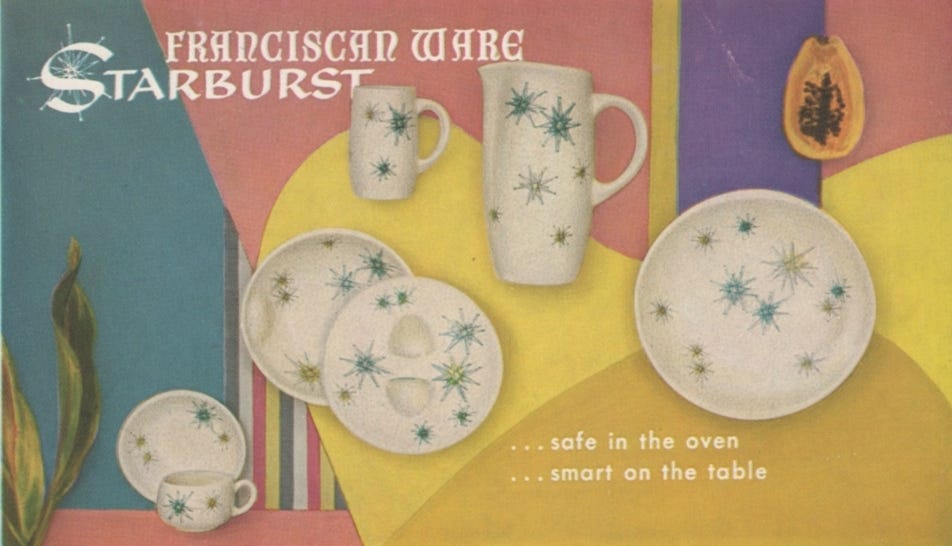

In the fall of 1991, after setting up and selling at the Glendale Pottery Show, I met with George T. James (1923-2003) at his home in Los Angeles, California. George James is best known for his Eclipse shape used for Franciscan Starburst tableware.

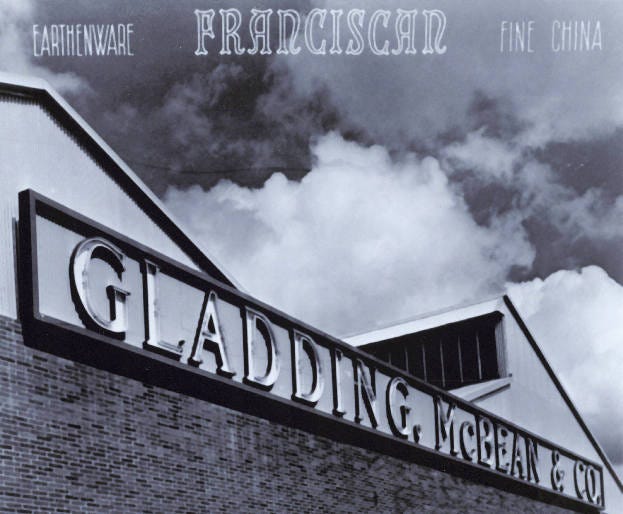

George James began as a control engineer for the Franciscan ceramics division of Gladding, McBean & Co. in 1950. James was promoted to designer in 1952. James left Gladding, McBean in 1963, becoming a free–lance designer for other companies. In 1966, James returned to work as a designer for the Franciscan Ceramics division of Interpace. In 1971, James was promoted to manager of the Design and Development Department. James left Franciscan in 1977 to continue his own free–lance work.

Among the memories and memorabilia James shared with me was a book he was writing based on his life. He gave me a printed copy of the chapter about his first experience at Gladding, McBean, a moment that set the course for his career. The book was never published.

When George T. James set out to find a career in ceramics, he envisioned stepping directly into the world of design and dinnerware creation. But reality had a different plan. His first attempt to secure a design position at Gladding, McBean in 1950 was met with an unexpected roadblock—there simply was no formal design department. Mary K. Grant was the Lead Stylist, overseeing all design. Yet, through persistence, personal connections, and an unwavering belief in industrial ceramics as an art form, James ultimately carved out a role for himself, laying the foundation for a career that would shape modern American dinnerware.

In his chapter titled "2901 Los Feliz," James recounts his first steps into Gladding, McBean, the initial disappointment of learning the company lacked a design department, and the surprising turn of events that ultimately led him to a career-defining opportunity. His narrative, originally filled with fictional names (now annotated with actual names when known)—captures the emotions and challenges of a young designer determined to find his place in industrial ceramics. composition for large-scale production, offered a hands-on education that would shape his approach to dinnerware design for decades to come.

2901 Los Feliz Blvd, by George T. James

Ernest [George James] slid out of the pick-up truck with a portfolio of his Art under one arm and a box of his own clay pieces under the other. From the sidewalk he said thanks to Steve the gardener who had driven him over from Pasadena. He said he hoped it wouldn't take too long. Steve said it was alright and wished him luck. Ernest Lake [George James] turned to walk up a long access road between bushiness properties facing the boulevard. There was a Payne's Nursery to the left on a corner and Rusty's 76 station to his right. Up ahead he could see a substantial company sign executed in decorated tile. It announced:

2901 LOS FELIZ BLVD

Estab. 1875

He could also see an open gateway and a small gate house on the right side of the road fifty or sixty yards in from the street. He liked the gate house because it looked to be made mostly of clay products. The long narrow bricks in its walls were of a shape he considered architecturally significant, and its roof was made of slate--a distant relative of all clay materials. Beyond the gate house he saw the pitched and odd-shingled roof lines of a large factory made up of a number of buildings. The jumbled sizes and shapes gave no idea of the vast complex of production that lay beyond his first impressions.

He stopped at the gate house at a countered window and asked for the Personnel Department. The guard on duty said, "That's easy," and pointed off to his right. "It's over there through the door at this end of that one-story building. Ask for Mr. Palme." Ernest [George James]'s head turned to follow the pointing finger as the guard said sign in here and enter the time." He dropped the portfolio down alongside his leg and signed his name to a pad on a clipboard and noted the time as 10:00 in the a.m. column. The date at the head of the sheet was August 13, 1950.

A few feet from the door to the Personnel office his mind crowded up with the all the good reasons why he knew he should be looking for a job in a place like this, along with his anticipation of the questions Mr. Palme might ask of him. He remembered also as he passed through the door what he had heard somewhere that working for this company would be like doing advanced study at a university devoted solely to the subject of clay. And he was nervous.

"Mr. Palme?" He asked of the only man he could see in the office. “I'm looking for employment as a Designer in your Dinnerware business. I'm a graduate of the New York State College of Ceramics and I have a portfolio here of my designs on paper and examples of my work in three dimensions." He said this straight out across fifteen feet of space to a man flipping through pages of paper held in his left hand

Several women at typewriters glanced up at him. "Yes, I'm Palme" the man said approaching him where he stood in front of the job application counter.” And I'm sorry to have to say this but we haven't had a design department as such in nine years. We have a vice president who runs the Dinnerware Division, and his wife manages all the design side of our dinnerware business."

"How about as a trainee or an apprentice?"

"No chance. There's just nothing like that available in this factory. Again, I am sorry." Still flipping the papers in his hands, he went on. “You might try Max Weil or Santa Anita Potteries. They're just around the corner a few blocks down on San Fernando Rd. They make dinnerware. And then there's the Bauer factory further on down just off the Arroyo Seco. They're all good sized outfits. Or there's a hundred other shops big and small all over the county making all kinds of ceramics. From fine china to Donald Duck. In big factories like this one all the way down to one man/woman backyard garage-scale operations. From lamp bases to ash trays, they're all over; All taking advantage of the decline of imports brought on by the war. So, all I can say is good luck. I'm sure you'll find something.”

"Thanks a lot." The whole adventure couldn't have taken more than ten minutes when he slid back into the pickup to face Steve's "Well how'd it go?”

“Can you believe it? They haven't had a design department in nine years." He sank into the seat. Steve started the engine. "And so much for starting at the top with the big boys." Ernest [George James] said. "Let's get out of here." He really hadn't started at the top. Maybe he started with the biggest, but he hadn't started at the top as he began to think of himself as an eastern snowball lost in the local palm trees.

The feeling didn't lose long because he was the guest of some older and established friends in Pasadena who knew of and understood his ambition to work in industry. This kind of ambition was different from the option of working as a potter in a studio on his own. Or teaching. His friend “D” was upset when she learned of the futile trip to Los Feliz Boulevard. At the first opportunity she asked her husband if he knew anyone in the 2901 Los Feliz organization.

“You must know someone over there I can talk to. Someone I might convince would then put this young man's talent to good use."

Her husband nodded. “It so happens I do know the head man. I could call him. I'll give him a ring tomorrow morning.”

“It's only two-fifteen now. Couldn't you just try him this afternoon? And please would you make the appointment for myself and this asset in the rough?" Her husband nodded again and went to the phone.

"Thank you my Dear."

His arrival at 2901 Los Feliz this time was different. Now it was “D” as a champion of the arts who drove him back to on appointment beyond the gate house and the discouraging office of Mr. Palme. He was worthy: an artist-potter who held the belief that Good Design and Bauhaus principles could uplift the ugly face of useful things. That he chose to do his best in industry was reason enough for her to make the effort on his behalf. They are on time for the appointment. He is nervous again until a secretary leads them into a high-ceiling and heavily paneled office announcing them to the President [Fred B. Ortman] of all 2901 Los Feliz Boulevard. The big man smiles all around. Shakes hands. Ernest’s [George James] too. Asks them to sit down. Mr. Palme asks a smiling question of D. "And how is that incomparable husband of yours? I am very much an admirer of him and his work."

"My husband is fine, thank you, and will appreciate your asking after him I'm quite sure. However, I’m imposing on your valuable time I do realize. But I do it to bring to your attention the potential of this young man as a unique contributor to the ongoing success of your enterprise. His background and aspiration make him especially suited to establishing a career in this,” she raises her arms and slowly turns back and forth at the waist, "in this your world of wonderful clay working.” Ernest [George James] is impressed.

So is Mr. Ortman, who says with some feeling "Oh, I'm sure we can find a place for his very obvious qualifications.” He pauses as if thinking something through. "The vice-president [Frederic Grant] of our Dinnerware division and his wife [Mary K. Grant] are on vacation for the next few weeks. She who is uniquely responsible for the design and originality of our very successful dinnerware lines and will talk with our young man here as soon as she and her husband return. I’m sure that can be arranged. In the meantime, I’ll introduce him to our vice-president for production, who will find something to keep him interested until our vacationers are back.”

He then pressed on the intercom button on his desk. “Gerri, would you see if Mr. C and Mr. B and Mr. G are about and ask them to step into my office for a moment. Please? Thank you." A few minutes later D. and Ernest Lake [George James] are a small reception line for introductions to three vice-presidents. They meet Production. They meet Research-Development They meet Engineering. With his final instruction to report to Mr. C's office the following Monday morning, the President (Fred B. Ortman] bids them "Goodbye." When they leave the President's office and the premises; Ernest [George James] knows he has been the beneficiary of the old who-you-know wisdom.

"Tensile strength." Leon T. the Research technician said this to him on his first day of employment. "That's what I'm doing now. With this machine I test the transverse strengths of fired clay body combinations and wind up with a factor of something called The Modulus of Rupture.' Interesting. He thought for a moment he heard Leon say modulus of rapture". Then he decided Leon knew what he was doing because he was easy to talk to. He was told to hang around with Leon in the Research Lab for a few days until someone else got back from vacation Everybody who might have something to do with his potential seemed to be on vacation The vice-president of Production told him during his Monday morning orientation that Ben B when he got back would be his supervisor and assign him things to do in the Quality Control Laboratory. Ben B had day to day responsibility for the technical standards of production for all company products made in the L. A. area. Implementation of technical standards insured quality control. Deep into his orientation the head of Production added that Ernest [George James] would be paid $275.00 per month: exempt from overtime. That meant Ernest [George James] had status as a salaried employee who might have to work an occasional Saturday but would be considered management level material Mr. C the production man emphasized this. He never once mentioned the dinnerware vice president or his wife.

People responsible for his destiny returned, finally. And after the first week he moved out of Research to a desk of his own in the Control Lab next door. Ben B was a direct man. He made it easy to understand what he expected as he ran Ernest [George James] through his new employee appraisal and decided that if Ernest [George James] could actually throw a pot on a potter's wheel, he might be of some use in the clay working section of the dinnerware operation. Ben B mentioned an opening for an engineer who would be responsible for maintaining quality standards for all processes and materials related to the earthenware clay body including its formation into dinnerware shapes. That meant from the beginning: where the clay body is put together up through the systems of forming all the shapes that make up a set of dishes there was need for a replacement and Ernest [George James] could be it. He thought he would like this: to be in at the start. He would catch the feel of the clay where the raw materials come together and things take shape. He sensed he could see and maintain connection to the pottery making urge he already knew. He would never feel strange or out of place at work on a clay shop floor. Ben B walked him through the factory and introduced him to production people he’d have to deal with every day.

What craft he brought to the job he put to use immediately, and he was surprised how much school-lab technical stuff had settled in his head alongside the fancier art and design criteria. Technical fundamentals came back, generating a new kind of creative excitement. Every day was a day spent balancing benign chemical forces. Clay had ways of its own. Until its properties were fixed by fire it was a combination of materials in a steady process of alteration. Daily, as it became his responsibility, the clay moved itself between acid and basic polarities and so altered its own viscosity Too much variation from the production standard and Ernest [George James] heard this one day, from an irate 'caster', bellowing across the full length of the shop in Oklahoma blue language: "Hey you! Where'd y'get this mud? Sears roebuck? I got five kids practically in diapers. If I don't make my incentive overage, I cain't feed my babies!" He found pride and a sense of power in the finesse he developed "doping" of 500 gallon tank of casting "slip." Adjusting very small additions of electrolyte, he'd weigh a sample for the ideal gravity. He'd run the sample through for fluidity. The tank would "age"--like wine in a great cask--for a day. He'd climb a three-step ladder the next morning and stir his forearm into the silk-smooth botch. I he'd draw his arm up in the highest hope the warm putty gray, fluid cloy would flow from his pursed fingertips in one uniform unbroken string. If it come down in thin scrawny drops or clung to his hand like Jell-O, he had trouble.

Mr. and Mrs. F. G. W. [Frederic J. Grant], the V.P. of dinnerware and his wife [Mary K. Grant], got back to work in the fall. Ernest [George James] got to talk to Mr. W [Mr. Grant] in December. Mr. W [Mr. Grant] decided that if Ernest [George James] had been successful in obtaining a diploma from "the only ceramic college in the U.S.", that was good enough for him and something of ceramic value must have adhered to Ernest [George James] in the process. Mr. W. [Mr. Grant] had been hearing Ernest was doing a good job in the Control Lab. He suggested Ernest [George James] keep at it and when a need for designer skills of the kind Ernest might offer arose, he, Ernest [George James], would be utilized without delay. Ernest [George James] asked after Mrs. W. [Mrs. Grant] if he might meet her and perhaps discuss areas of common design interest. Mr. W. [Mr. Grant] said Mrs. W. [Mrs. Grant] did not keep a standard office schedule and advised Ernest [George James] to be patient and to keep up the good work.

The days and months of three years passed over him. Not without satisfactions: He liked the detective story slant to his daily round of problem solving. It came as a surprise that he was learning to channel his imagination of what he thought was happening into a format that fit his observation into summaries of facts useful to others. He even wrote a few technical papers. Posing, in one instance, as on expert on 'pinholing' (a casting shop problem) and addressing the local chapter of the Ceramic Society. He felt it was all in preparation for the time he would be called upon to design some of the world’s great crockery. In the meantime, there were those who "educated" him. Doc 0., for one -- did original research projects for dinnerware--would illustrate how his imagination was being organized into useful patterns: "You take two thin panes of glass with a film of water between them." Doc 0. says this, as he picks up two clean microscope slides and wets them under a faucet. "Bring them together and they slide against one another very easily. But, here now, try prying them apart." Doc 0. hands him the demonstration and goes on, "The slides resemble clay molecules in shape and organization, and the water is just there, it's incidental, just as it come from that faucet, or as it might fall from the sky into a bog of clay." The slides slip and slide between his fingers. They won't pry. He cannot unstick one slide from the other. He knows the slides will crack first. we “On one axis, the clay molecules ore lubricated by the water and slide with incredible ease against each other. On the opposition axis the same water seems to act like "glue" and the molecules hang together. And that's what makes clay unique: plasticity. Push clays around when it's wet and it holds its shape. A mud pie has no plasticity. Plasticity: that's what makes clay different from ice cream or a sand castle."

And there were the times he felt things were not going well with some part of his responsibility, or he hated someone else's opacity enough so that he had to get away for a few minutes. He'd take a walk. It did not show from the boulevard but there were forty acres of 2901 Los Feliz to walk around on. Tucked up in a corner of Los Angeles between Griffith Park and the city of Glendale, in times of fuss or boredom, he explored all of it. He would cross the dinnerware and tile plants and pass out a side door to where the air seemed better for the wet clay smell Out there, out from underneath the dusty roofs, a sewer pipe operation sprawled in the open sir across most of the back acres. Heavy-duty, industrial, tonnage: these were qualities and fables suited to the most straightforward manufacturing system on the property. And, giants worked in hard hats, on giant forklifts and giant tractors moved huge shapes of clay pipe bells back and forth between the biggest kilns he’d ever seen. Great slugs of common clay extruded from huge dies pressured in columnar machines forty or fifty feet tall made pipe in diameters from six to thirty-six inches. There was a dozen of them, in clusters of four. Kilns: thirty-six feet in diameter. Round down draughts, they were called. Gas fired monsters. It took twelve days to full cycle one of these 'giants'--six days up to 2000 for six days to cool the fired pipe back down: one of his dinner plates or cups or saucers cycled in less than twelve hours. Thee soapy, olive drab clay--before fire turned it pinkish red--would return to ditches in the earth as miles and miles of urban tube. Its integrity and fired beauty would never show above the ground. His occasional amble often cleared his thought.

© 2025 George T. James. 2901 Los Feliz Blvd. Used by permission the Franciscan Ceramics Archive. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations used for review or scholarly purposes.

It has been a pleasure sharing this autobiographical chapter, offering a firsthand glimpse into George T. James' early experiences at Gladding, McBean—where industrial ceramics and creative vision first converged in his career. His story captures the determination and ingenuity that shaped his path, revealing the human side of mid-century design.