The Evolution of Franciscan Ware: Crafting an American Icon

Five Decades of Design: The Rise and Legacy of Franciscan Ware

In our prior post, we began our journey into the world of Franciscan Ceramics—a brand that has captured the imagination of collectors and enthusiasts for decades. We celebrated its artistry, innovation, and enduring impact on American culture, providing insights into its legacy and the research that has preserved its story. Now, let’s take the next step in exploring Franciscan Ware’s journey by diving deeper into its product evolution, historical context, and design innovations from 1934 to 1984.

A Legacy of Handcrafted Elegance

Born in the depths of the Great Depression, Franciscan Ware was far more than tableware—it reflected resilience and ingenuity during one of America’s most challenging economic periods. Beginning in 1934, Franciscan’s designs brought sophistication and practicality to American households, transforming every day dinnerware into an artistic statement. From its humble beginnings in solid-color glazes to its revolutionary embossed hand-painted styles, Franciscan Ware captured the imagination of a generation seeking beauty and durability in uncertain times.

The Great Depression Sparks Creativity

The economic hardships of the 1930s compelled Gladding, McBean & Co. to adapt from architectural ceramics to consumer goods, mirroring the strategies of many businesses responding to plummeting construction demand. In the same year that Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the New Deal programs to revitalize the American economy, Gladding, McBean repurposed its Tropico Potteries factory in Los Angeles to create the Franciscan Pottery line. This innovative pivot gave Americans affordable, beautifully designed tableware that brightened homes during a time of widespread adversity.

Its first offering in tableware, El Patio Tableware, debuted in 1934. El Patio’s vibrant pastel and jewel-toned glazes reflected the color and creativity Americans craved as they rebuilt their lives. Competing with regional brands like Catalina and Bauer, El Patio became a symbol of California’s ceramic artistry in the mid-1930s.

Alongside its tableware, Franciscan expanded into decorative art ware in 1934. These early art ware lines, developed alongside the El Patio collection, showcased bold solid-color glazes and inventive forms—elements that would later be influenced by the creative innovations of Catalina Island Pottery. Gladding, McBean acquired the assets of Catalina Island Pottery in 1937, the techniques and design elements—such as their striking glazes—found their way into Franciscan's offerings.

In 1936, as the U.S. geared up for recovery through public works projects and urban infrastructure expansion, Franciscan introduced Coronado Tableware, which featured swirling ribbed textures that embodied sculptural grace. These designs mirrored the budding optimism of the pre-war years, complementing the burgeoning mid-century modern aesthetic.

World War II and Revolutionary Designs in the 1940s

The 1940s ushered in a period of bold creativity and adaptability for Franciscan Ware. Against the backdrop of World War II, Franciscan Apple debuted in 1940 as the brand’s first hand-painted embossed dinnerware pattern. Its rustic raised-relief design of apples and leaves, paired with hand-painted glazes, resonated with wartime America’s emphasis on simplicity and tradition. Originally adapted from a Weller Pottery pattern called "Zona," Apple was reimagined by Mary K. Grant to reflect Franciscan’s signature style.

Following on the success of Apple, Desert Rose was introduced in 1941. Its delicate floral motifs—pink blossoms paired with brown stems—became a symbol of warmth and family gatherings during an era when loved ones were often overseas. Franciscan’s ability to balance artistry with practicality echoed the wartime ethos of resourcefulness.

However, wartime restrictions presented significant challenges to the ceramics industry as materials like clay and metal oxides were diverted for military use. All art ware was discontinued by 1942, and no new shapes were introduced for the duration of the war.

Post-War Boom and Mid-Century Modern Innovation (1946–1961)

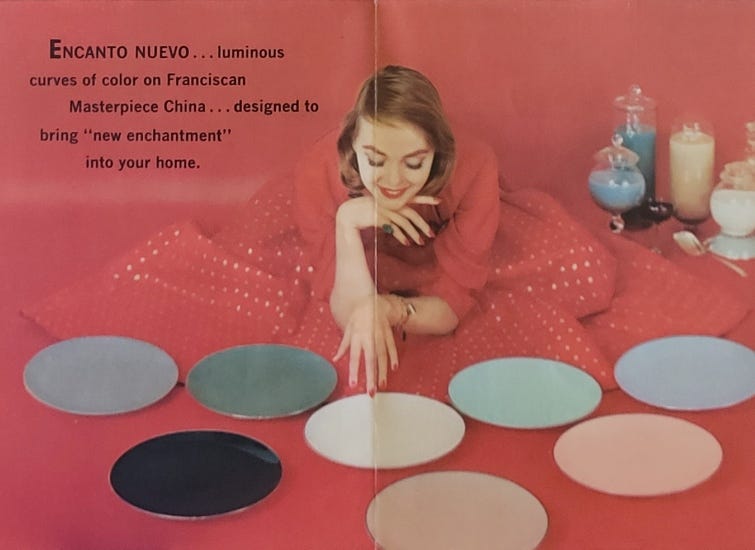

As the United States entered a period of post-war economic prosperity, Franciscan Ware reflected the optimism of the era. In 1948, Franciscan debuted Encanto Fine China, a modern tableware line designed by Mary K. Grant that featured soft curves and glossy finishes. Recognized by the Museum of Modern Art’s 1951 Good Design Exhibition, Encanto exemplified mid-century America’s cultural dynamism.

As America entered the space age, Franciscan continued to innovate with its Modern Americana initiative, launched in 1954, introduced futuristic designs like Eclipse and Flair, created by George James and Mary Chalmers Brown. These patterns embraced the space-age dreams of the era, reflecting America's excitement over technological achievements like the establishment of NASA in 1958.

In 1955, Franciscan ventured into sculptural art ware with Contours Fine China, a collection that emphasized sleek lines and abstract decals. While not a commercial success, Contours reflected the avant-garde artistic experimentation of the Cold War era, paralleling America’s evolving cultural narrative.

Social Change and Continued Innovation (1962–1979)

The transformative 1960s brought profound cultural and social shifts, and Franciscan Ware adapted by embracing both tradition and innovation. In 1962, Gladding, McBean merged with Lock Joint Pipe Co. to form International Pipe and Ceramics Corporation (INTERPACE), expanding its operations both nationally and internationally.

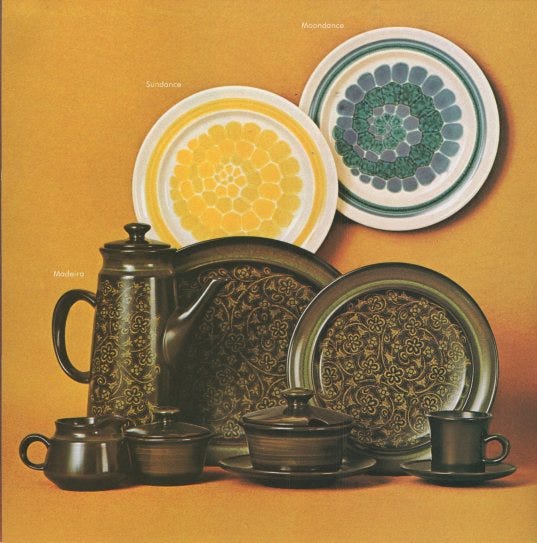

During this period, Franciscan introduced designs that resonated deeply with the consumer. The Madeira collection, which featured rustic stoneware inspired by artisan craftsmanship. This pattern resonated with the back-to-nature movement of the late 1960s, becoming one of Franciscan’s best-selling lines.

By 1973, Franciscan introduced the Discovery collection, showcasing experimental designs with wax-resist decals and hand-applied dot details. Patterns like Tahiti, Terra Cotta, and Topaz exemplified Franciscan’s embrace of bold, contemporary aesthetics. Terra Cotta and Tahiti were later featured in the California Design Nine Exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum, cementing Franciscan’s status as a modern design innovator.

Amid growing economic pressures, INTERPACE restructured its operations, selling its Lincoln plant to Pacific Coast Building Products in 1977, shifting its focus exclusively to dinnerware and technical ceramics. This move set the stage for the sale of Franciscan Ceramics Inc. to Wedgwood Ltd. in 1979.

Corporate Transition and Legacy Under Wedgwood (1979–1984)

The years between 1979 to 1984 marked a pivotal chapter for Franciscan Ware and the American economy. When INTERPACE sold Franciscan Ceramics Inc. to Wedgwood Ltd. in 1979, it reflected a broader trend of international investment and consolidation within American industries during this time.

This period coincided with significant challenges in the U.S. economy, including high inflation and foreign competition. By 1980, Ronald Reagan’s presidency ushered in policies aimed at economic recovery, including deregulation and tax reforms under Reaganomics. While these changes stimulated growth in some sectors, traditional manufacturing industries faced mounting pressures.

Under Wedgwood’s ownership, production of Franciscan’s most celebrated patterns—including Desert Rose, Apple, and Fresh Fruit—moved to the Johnson Brothers facility in Stoke-on-Trent, England, marking the globalization of the brand. The closure of Franciscan’s Los Angeles factory in 1984 ended its U.S.-based production, but its most iconic patterns continued to thrive under Wedgwood’s stewardship.

During this transitional era, cultural shifts also influenced consumer habits. Disposable and inexpensive informal tableware gained popularity in American households. Yet, Franciscan Ware’s enduring designs stood apart, offering a timeless charm that resisted fleeting trends and upheld the values of craftsmanship and artistry.

Legacy That Lives On

Between 1934 and 1984, Franciscan Ware defined how Americans celebrated beauty in everyday life. Its hand-painted patterns like Apple and Desert Rose, its innovative fine china lines like Encanto, and its embrace of modern design trends like Madeira and Discovery captured the spirit of a changing nation.

Franciscan Ware wasn’t just dinnerware—it was a reflection of resilience, creativity, and artistry. Today, its cherished designs continue to grace dining tables around the world, preserving the legacy of an iconic brand that shaped American culture for half a century.

Looking Ahead: Unlocking Exclusive Stories

Thank you for joining me on this journey through the history of Franciscan Ware. As we continue to uncover its fascinating legacy, I’m excited to share that future posts will remain accessible to everyone—for free. These posts will explore compelling topics such as deeper dives into Franciscan’s iconic designs, the artisans who shaped its legacy, and the historical context that brought it all to life.

For those seeking even more exclusive insights, including behind-the-scenes details and untold stories, I’ll also be offering subscriber-only content. These posts will take a closer look at topics that showcase the depth of Franciscan Ceramics’ artistry and innovation.

The first subscriber-only post will highlight the legacy of Annette Honeywell, the visionary designer behind iconic Franciscan patterns like Desert Rose. In addition to her work at Franciscan Ceramics, we’ll explore her lasting contributions to the fields of art and design, celebrating her influence as both an innovator and an artist.

I look forward to sharing even more engaging stories and insights with you. If you haven’t already subscribed, I invite you to join me as we continue to honor the artistry and heritage of this remarkable brand. There’s so much more to discover—together.

© 2025 James Elliot-Bishop, The Franciscan Ceramics Chronicle. All rights reserved. This content is protected under copyright law. No reproduction or distribution without permission.